Intro

I originally started this essay with the title “when and how to repeat code properly.” One day I had the urge to delete some code from production to make it cleaner, but then I thought 'Do I really know if I'm improving your codebase by removing that code?' I didn't. As I was writing the essay on the original topic, I realised there's a shared pattern between the rules of programming and non-programming. I wrote this essay to think of the rules you face in your lives, and how to interact with the rules to get the best out of them.

Don't repeat yourself - DRY

DRY is a programming principle, but in this essay, I will call it a rule, and use the underlying rationale behind DRY principle as the actual principle.

Let’s look at a rule in programming; Don’t repeat yourself - DRY.

The principle of this rule is “Every piece of knowledge must have a single, unambiguous, authoritative representation within a system” as written in the book The Pragmatic Programmer. The purpose behind this principle is to write code that is easy to manage and update.

- Rule: Don’t repeat yourself.

- Principle: Every piece of knowledge must have a single, unambiguous, authoritative representation within a system.

- Purpose: Write code that is easy to manage and update.

DRY rule exists in the world of programming. The principle is more applicable to other parts of the world. If you just substitute write code with develop system, the last part is almost applicable to any field. If you are building a bridge, you want to build in a way so it is easy to fix and maintain. Same with designing a piece of furniture, an instragram-able cafe, you name it. Before there was any programming language, humanity built a million things in a million other ways.

When to override a rule

In real world codebase, there is a lot of legacy code. Legacy code is code from some system in the process of being deprecated. Feature flag is one way you can deal with legacy code while releasing new features. If you are rendering different versions of the same component, it is tempting to implement a conditional check on the feature flag within the component. But this is prone to become a file full of multiple different feature flag checks of different levels. This makes the code difficult to read. Quite often in production, we have to develop with speed from the business needs. Code that doesn't read easy becomes bad code with this need.

One alternative is to create two files that would render the same component, but with different names such as component and legacy_component. As these two components will be rendering similar things except certain sub-parts, a lot of the code will be repeated. Now you see this goes against the DRY rule. One engineer could raise this as bad code.

But let's go to the principle, where the DRY rule comes from. > Every piece of knowledge must have a single, unambiguous, authoritative representation within a system.

If the component becomes a whole mess of conditional check, it is no longer unambiguous neither an authoritative representation. If you separate to a normal vs. legacy component, although some code is repeated, each component will be clearly doing one thing: "Render something if it's version x.x.". So what do you do here?

We should divide them into two components! Yes, you would be repeating code. But as I said above, code that is easier to read, is easier to update. And this will also follow the purpose behind the principle > Write code that is easy to manage and update.

When a rule and principle are telling two different things, you should follow the principle.

Relationship between rules and principles

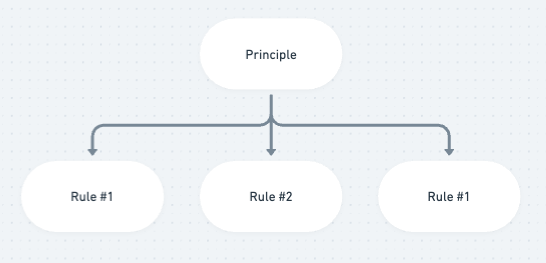

- A principle has a 1-to-many relationship to rules.

- Principles exist before rules; rules are born out of principles.

A principle is a way to do something. Rules are specific instructions of ways to do something a certain way. So, to write code with single, unambiguous, authoritative representation within a system, you can follow the DRY rule and many other rules. So as new languages and frameworks appear, you need to modify existing rules, add new rules, and deprecate older rules.

These two points lead to the rationale that when a principle and rule tells you two different things, follow the principle. After all, rules are action items that develop naturally a side effect of existing principles.

Why are rules useful

So you might ask, why do rules exist? Are they actually helpful?

Yes, they are.

Rules are easier to follow. Even a novice programmer can read about the DRY principle and follow the rule. And as rules are more specific action items, it is easier to spot them when they are broken. If you are only told about the underlying principle that there should be a single representation of an idea within the system, this would leave you in more ambiguous state. If you are told to write code that is easy to maintain and update, you are often left with the question “How the fuck am I supposed to do that?”

It leaves you in this ambiguous state because there are many different ways to do this. DRY is not the only way you can write maintainable code. There are a dozen principles that would help you get there, and per each principle, there are a dozen rules that would get you to that principle. So there are dozen^2 methods to do something the right way. Even if you know how to do this, deciding how to do it every time would slow you down. As I wrote in “Don’t be a perfectionist”, most times you should spend just enough time to make it good enough.

More importantly, it is really hard to understand a principle well enough to know how to follow it well within time constraints. Often when you are writing code, you don't have an indefinite amount of time. you don't have the time to sit down and think of every line of code. The reason you have simple rules to follow in variable naming is for this. Not all boolean values will be most well represented by is_x or has_x, but most of the time this will be clear enough. So this is a rule - or a convention, whatever you want to call it - that you follow in the industry.

Some principles are simply abstract and difficult to follow. It’s easy to know about the Single Responsibility Principle, but that doesn’t mean you know how to constantly write code that follows this. It is often easier to know a rule than the principle, and it takes the latter to properly execute it.

So rules help you do something that will likely follow a principle within time constraint, with a decent level of understanding of the underlying principle. Rules act as guardrails to keep you in the boundaries of the principle.

Once you understand the principle behind the rule by heart, you start seeing the missing puzzle pieces between rules. Just like test coverage, there is rule coverage which would be all the right things you need to follow the principle. In the ideal world, the engineer will be able to run all the tests after writing some kind of code, and if all passes, they know the code didn't break anything. And as an engineer can remove or update existing code when they know their code is right, but an existing test failed, knowing the principle will give you the confidence to start overriding rules.

Not just code

Rules and principles exist everywhere. It's not just the world of programming. I wrote about programming because I do it a lot, so it is easier to explain in those terms.

We can write this whole essay about the rule green-go, red-stop and the principle We should cross the road when there are no cars coming your way.

We can also write it about art. If one of the principles of a successful artist is to give the public an impression, Henry Rousseau did it well - a lot of us have heard of him. He was originally a tax collector and didn't have a formal art education, which led him to paint without following conventional art rules, such as perspective.

Look at the portrait below. Look how out of proportions certain things are. But his paintings caught people's eyes.

We shouldn't try to avoid rules, neither blindly follow them. Avoiding rules won't get you faster to understanding principles, and following rules blindly will prevent you from properly understanding principles. But once you follow rules consciously, you will have these Eureka! moments where it suddenly clicks. It makes sense why you were told to do something a certain way. DRY makes sense, not because a senior dev told you so, but it does lead to better code. Putting your guard up and chin down in boxing starts making sense as you suffer a nasty punch in your chin one day.

So you should follow rules. But follow with awareness. Give the rules enough trust to follow by default, but question if they would always be the best way. Step by step, you will get closer to the principle. If there seem to be no concrete principle behind a rule, it might be a new abstract principle. In those rare and lucky cases where you spot a rule born before the principle, you will be able to reverse engineer the principle out of the rule. This will put you ahead of every one else in the game.

Even before Andy Hunt and Dave Thomas wrote The Pragmatic Programmer, there was the principle to write good code that is easy to manage. One day they sat down, reviewed the principle, and decided they can write them into rules. But you have to become good. You have to know the principles by heart. This isn't easy. But once you get there, and have a bit of curiosity, you will start discovering these small areas not covered by the web of existing rules.

---

Thanks to Cristian, Nathan, and Dzmitry for reading this essay.